A Core Vocabulary for Latin Classes

Which words should the learners be able to fall back on when reading Latin original texts, i.e. which basic vocabulary can be assumed to be ideally (!) learned during the first years of language acquisition? Are existing core vocabularies really representative for the following original Latin texts?

The Bamberg Vocabulary (BV)

Most Latin textbooks published after 2005 are based on the so-called Bamberg Vocabulary (BV), which was published in 2001 (publication title: Adeo-Norm (Utz 2008)). This one was created in a project supported by Buchner-Verlag (Bamberg) with the aim of reducing the amount of Latin learning vocabulary to the necessary level (i.e. the 'correct' choice of vocabulary). One of the initiators, Clement Utz (Utz 2000), points out in this context that the didactic considerations regarding the scope and selection of a learning vocabulary for Latin teaching have not been reflected since the 1970s of the last century, although the teaching conditions (amount of hours per week/years, heterogeneity of learners) have changed considerably. In order to create transparency for the didactic decisions in the creation of this basic vocabulary, Utz reports in detail about the project in a "workshop report", so that in the following the selection criteria, the methodological procedure, the data basis, the presentation of the results and any problems of the BV can be briefly presented. This makes sense with regard to the Callidus project, not only because the BV can usually be regarded as the standard for the learning vocabulary of the newer Latin textbooks, and thus forms the vocabulary basis that must be used in the reading phase (adressed users of CALLIDUS). The BV can also be regarded as the 'gold standard' of the vocabulary customers for Latin Classes, since its development has been methodically reflected as well as largely transparently and comprehensibly presented.[1]

Selection of texts

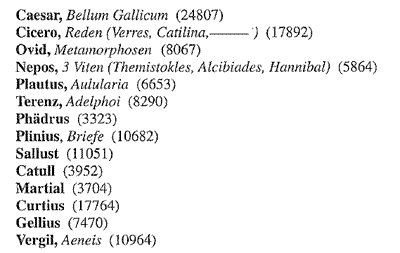

Since " die Originallektüre gehaltvoller lateinischer Texte nach wie vor Hauptziel des Lateinunterrichts überhaupt und somit auch der Wortschatzarbeit ist " (Utz 2000, 151), a new basic vocabulary to be created must take into account the authors and works of the reading phase in Latin class. For this reason, the text corpus was derived on the one hand from the curricula of the eight states with the highest number of 'Latin' students in absolute numbers (Bavaria, North Rhine-Westphalia, Baden-Wuerttemberg, Lower Saxony, Hesse, Rhineland-Palatinate, Schleswig-Holstein and Saxony), and on the other hand, references of the "einschlägigen Lektüreausgaben" (Utz 2000, 155) were compiled by comparing three text editions of an author or work and using the corresponding text passages for the basic corpus. However, the text passages that were exclusively reserved for basic resp. advanced course instruction in the 12th or 13th grades were omitted because vocabulary learning as a "Lernen auf Vorrat gerade bei fremdsprachlichen Vokabeln, die vom lernenden Schüler trotz aller Vernetzungsmöglichkeiten vorwiegend als speicherbare Einzeldaten aufgefasst" (Utz 2000, 156) was not further supported. For both sources a comparable frequency sequence of authors and works relevant for Latin classes was found (descending)[2]:

- Caesar; Cicero speech

- Ovid, Metamorphoses; Nepos; Comedy; Phaedrus

- Pliny (minor); Catullus

- Sallust; Martial

- Curtius; Gellius

- Virgil, Aeneid [3]

The total volume of the corpus thus assembled contained 140,482 word forms (~ tokens). After deducting the 7156 references for names, 133,326 word forms remained for analysis (see Fig., Utz 2000, 153).

The Query-Corpus as a basis for frequency statistical investigations

The selected text passages were then lemmatized with the help of the scientifically annotated query corpus (Heberlein 1990), in the case of new text passages also desambiguated, and then frequency-statistically evaluated (ranking). [4] From this structured data material (7154 lemmas ~ types), a basic vocabulary of 1248 words was determined, which allows a (statistical) text coverage of 83%.

How does the amount of 1248 lemmas come about?

Each lemma was included in the basic vocabulary if, firstly, it occurred at least 16 times in the text passages and, secondly, if it was found in more than three ancient authors. [5] A calculation of the text coverage for the underlying corpus resulted in the 83% already mentioned, i.e. with the 1248 words of the basic vocabulary (fundamentum), 83% of all words in the referenced Latin texts could be "translated". In order to achieve a higher text coverage, learners would have to 'cram' a disproportionate amount of additional vocabulary - for a text coverage of 100% this would mean an additional 6,000 words (Utz 2000, 158). As a consequence of this reduction of the basic vocabulary, words that were previously part of the so-called "cultural vocabulary" (e.g. mundus, ambitio, medicus, transportare) during language acquisition with textbooks were no longer used as learning vocabulary.

The presentation of the basic vocabulary

At the time of his report, Utz is particularly aware of the many ways in which lemmas could be sorted in a way that is conducive to learning: by subject fields (subcategory: word fields), lexeme fields, morpheme fields, collocation fields, and syntactic fields. However, he also recognizes the problems associated with this allocation, e.g. the meagerness of a field, as there could be only a few examples in the basic vocabulary. [6] De facto, the BV is now offered in alphabetical list form, in which, however, learning-promoting clues have been integrated in the outermost column.

Opportunities of the BWS

To consider from a didactic perspective how to reduce the learning vocabulary in Latin class in a meaningful way, offers the possibility to discuss the work on learning vocabulary in addition to the discussion about a uniform text basis. Furthermore, due to the chosen method, objectively measurable criteria are applied to the selection of words, which allow for a broad acceptance of the selection because they show conclusiveness and impartiality. The pre-sorting of the lemmas according to frequency statistical significance (the 500 most important words, basic vocabulary with 1248 words, author-specific supplements) can be seen as a significant opportunity for Latin classes, because it clarifies the spiral-like process of language acquisition and, through supplements, enables a demand-oriented adjustment of the learning vocabulary for the reading phase. In particular, this 'modular principle' could be further developed to create and use needs-oriented vocabularies (100, 200, 500, 1000 etc. most important words, author vocabulary, genre vocabulary, cultural vocabulary).

And finally, a few problems

As the actual presentation of the BWS in the analogous printed edition already shows, the presentation options of the learning vocabulary are so limited due to the linearity inherent in a book that one has returned to an alphabetical list, although even the initiator of the project knew about the difficulty of this form of presentation. Furthermore, due to space constraints, the learning aids are offered selectively and in a compressed form, so that above all extensive visualizations are missing. The underlying text base, which both ignored curricula of eight German states and only represented a snapshot of existing reading books (end of the 1990's), must also be seen as problematic [7] This means that the BV can only be updated if the entire process of creating the vocabulary is run through again. In addition, from a statistical point of view, the underlying text volume can be considered too small, so that unrepresentative clusters of individual words may not be compensated for sufficiently. In any case, a broader text basis - e.g. through whole corpora of certain authors - suggests that a greater text coverage could be achieved with the same amount of learning vocabulary (Freund and Schröttel 2003, 204).

❮ back forward❯

Bibliography

Freund, S. & Schröttel, W. (2003). Non quot, sed qualia. Wortstatistische Überlegungen zum Ausgangscorpus einer lateinischen Wortkunde. Forum Classicum 46 (4), 200–205.

Heberlein, F. (1990). Computergestützte Textrecherche im Lateinischen. Anregung 36 (2), 83–90.

Utz, C. (2000). Mutter Latein und unsere Schüler - Überlegungen zu Umfang und Aufbau des Wortschatzes. In P. Neukam (Hrsg.), Antike Literatur - Mensch, Sprache, Welt (Dialog - Klassische Sprachen und Literaturen, Bd. 34, S. 146–172). München.

Utz, C. (2008). Adeo. Das lateinische Basisvokabular (Bamberger Wortschatz, 1. Aufl.). Bamberg: Buchner.

[1] With other lexicologies, e.g. Langenscheidt's basic Latin vocabulary, Utz shows by means of quotations that the compilation of the word lists evades review and thus an assessment by the users.

[2] Supplementary proposals, e.g. Vulgate, Cicero letters, Legenda aurea, were not considered. Here, a limitation of the BV becomes apparent: Its vocabulary is not geared to late antique, Christian, medieval or modern texts, so that the text coverage to be achieved is likely to be significantly below the value for works of the classical period.

[3] Although Utz places his project under the heading of transparency, it is not clear in his report which parts of the text are concerned.

[4] The rankings between the BV and the entire Query-Corpus sometimes differ slightly (cf. Freund and Schröttel 2003). This can be attributed to the selection based on the school context.

[5] Words that occurred at least 16 times, but only with fewer than three authors, were assigned author-specific vocabularies.

[6] He weighs up the pros and cons for the common forms of representation - although subject fields do sort, they also cause interference if the conceptual nuances are not clear (scelus - crime; facinus - crime) - and ends aporetically.

[7] It is certainly worth discussing whether it is advisable to omit philosophical or post-classical passages, e.g. in Freund and Schröttel (2003). But if one wants to reduce the learning vocabulary and e.g. philosophical texts are only read in a very late phase of Latin teaching, then the conscious omission of these text passages seems reasonable.