MERGE X TRANSMIT Data Brief #2: Food insecurity in Lebanon and the potential ripple effects of the war in Ukraine

In this report we present novel data on the economic wellbeing, food security and migration aspirations of the Lebanese and Syrian population in Lebanon, collected between December 2021 and January 2022. By sharing these preliminary results, we seek to provide an understanding of the extent of the economic vulnerability in Lebanon before the onset of the war in Ukraine and to help anticipate its potential ripple effects.

By Dr. Simon Ruhnke and Dr. Nader Talebi

By Dr. Simon Ruhnke and Dr. Nader Talebi

Download the Pdf version here.

Background

A multitude of crises have left the Lebanese state and economy in a highly precariou

s situation. Under the already strained humanitarian conditions in the country, the Russian attack on Ukraine in late February 2022 and its impact on the global food supply poses a grave risk to food security and may render life unsustainable for large parts of the population in Lebanon.

In this report we present novel data on the economic wellbeing, food security and migration aspirations of the Lebanese and Syrian population in Lebanon, collected between December 2021 and January 2022. By sharing these preliminary results, we seek to provide an understanding of the extent of the economic vulnerability in Lebanon before the onset of the war in Ukraine and to help anticipate its potential ripple effects.

A Crisis within Crises

Beyond the tremendous harm it has caused for the Ukrainian people, the Russian invasion of Ukraine endangered the global food supply as many countries around the world rely on importing foodstuffs, particularly, wheat from one or both of these countries. However, as it is evident in the case of the COVID pandemic, as much as it is a global crisis, it is not experienced similarly everywhere and by everyone around the world. The impact of the impending food shortage will be felt hardest by politically and economically weakened countries. Lebanon, in the midst of an acute political and economic crisis since 2019, is one such country and heavily reliant on wheat imports from the conflict region. Imports from Ukraine account for 66% of total Lebanese wheat consumption while another 12% stem from Russia (FAO, 2022). However, to understand the severity of the food security problem in Lebanon one needs to have a look at the situation before the unfolding of the recent events in Ukraine.

Almost a year ago the World Bank warned that the economic crisis in Lebanon is among the top three ‘most severe crises episodes globally since the mid-nineteenth century’. Exemplary for this crisis is the disastrous situation of the National currency which has lost more than 90% of its value since 2019 with several (un)official exchange rates emerging. This means the minimum wage decreased dramatically from a monthly equivalent of 450$ before the crisis to less than 30$ these days. At the same time, the main response from Banque du Liban, the country’s central bank, has been cuts on subsidies in particular regarding basic commodities resulting in one of the highest inflation rates worldwide in consumer products. As of January 2022, the annual inflation rate soared to 239.69% with a 483.15% increase in food prices (Central Administration of Statistics). Despite all measures and capital control to prevent a total financial collapse, the shortage of Dollars limits the state's capacity to respond to the developing global food crisis. However, this is not the only issue considering the Lebanese governance structure, which faces a political deadlock preventing it from providing basic services such as electricity.

Apart from the ongoing crises, Lebanon is particularly vulnerable to the current global shortage of wheat as it lost the main importing station and grain silo in the Beirut blast (August the 4th 2020), one of the largest non-nuclear explosions ever recorded. The explosion was caused by 2,750 tonnes of highly explosive ammonium nitrate that were poorly stored and neglected at the port of Beirut for 6 years. It is estimated that the explosion left at least 200 dead, 6,000 injured and 300,000 displaced. Moreover, apart from the port it massively damaged public buildings and private property amounting to ‘between US$3.8 and US$4.6 billion in damage to physical assets’ (World Bank, 2020). Both causes and consequences of the blast have contributed to the political crisis in the country. Both causes and consequences of the blast have contributed to the political crisis in the country and exemplify the scope of political corruption in the country. The current storage capacity of silos in Lebanon is only enough for 6 weeks, and the state is struggling to find a replacement for wheat import and its necessary finances.

The food crisis is not only a danger to approximately 6.8 million Lebanese citizens in Lebanon. The country, while not a signatory of the 1951 Refugee Convention, hosts the highest number of refugees per capita worldwide. In contrast to the Lebanese government’s repeated statements emphasizing that Lebanon is not a country of refuge, more than 1,5 million Syrian refugees reside in the country in addition to nearly half a million Palestinian refugees who live there some for generations. Due to a lack of systematic integration policies and sustainable income opportunities, large parts of the country's refugee population remain in need of support from international and non-governmental organizations.

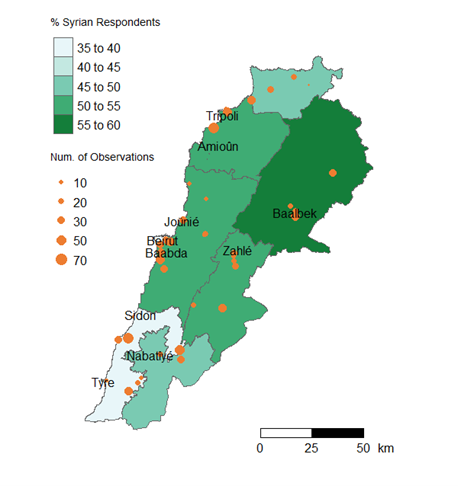

Data

The Data presented in this brief was collected in a face-to-face survey conducted in Lebanon as part of the TRANSMIT research project (s. Box 1). Data collection took place between December 2021 and January 2022 (prior to the Russian attack on Ukraine) across 39 sampling locations. The 501 Syrian and 509 Lebanese respondents (henceforth referred to as the sampling strata) had responded to a larger randomized survey conducted in the previous year, that was designed to provide a representative sample of the Syrian population in Lebanon, as well as their Lebanese host population residing in the same neighborhoods. While broad in its geographic coverage (s. Figure 1) the results presented below should thus not be understood as representative for the entire Lebanese population, but rather as a relative comparison of the living conditions of Lebanese and Syrians in shared neighborhoods.[1]

Figure 1: Approximate sampling locations,TRANSMIT Lebanon Follow-up Survey, 2021/22

The demographic composition of the sample is displayed in Table 1. The gender balance in both Syrian and Lebanese strata is close to even, while Syrian respondents are on average younger and live in larger households.

|

|

Host (N=509) |

Syrian (N=501) |

Overall (N=1010) |

|

Gender |

|

|

|

|

male |

244 (47.9%) |

244 (48.7%) |

488 (48.3%) |

|

female |

265 (52.1%) |

257 (51.3%) |

522 (51.7%) |

|

Age Group |

|

|

|

|

15-29 |

169 (33.2%) |

192 (38.3%) |

361 (35.7%) |

|

30-44 |

167 (32.8%) |

226 (45.1%) |

393 (38.9%) |

|

45-59 |

119 (23.4%) |

70 (14.0%) |

189 (18.7%) |

|

60+ |

54 (10.6%) |

13 (2.6%) |

67 (6.6%) |

|

Household Size |

|

|

|

|

Mean (SD) |

3.82 (1.63) |

5.04 (2.08) |

4.43 (1.96) |

|

Median [Min, Max] |

4.00 [1.00, 11.0] |

5.00 [1.00, 13.0] |

4.00 [1.00, 13.0] |

Table 1: Sample Demographic Composition, Source: TRANSMIT Lebanon Follow-up Survey, 2021/22

Results

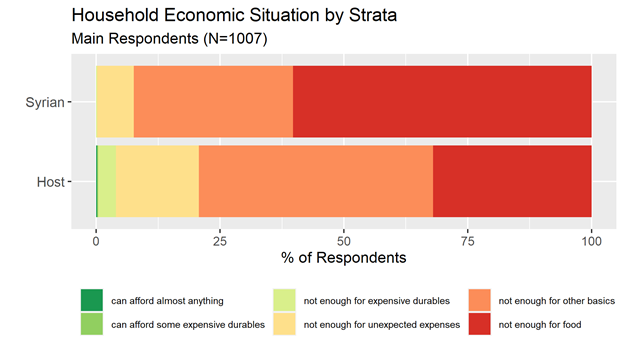

Figure 2: Relative frequency of self-reported household economic condition categories by sample strata, Source: TRANSMIT Lebanon Follow-up Survey, 2021/22

At the time of data collection, nearly all respondents in our sample appear to have been negatively impacted by the ongoing economic crisis in Lebanon, with 94.3% of our sample reporting that their households' general living conditions are worse than two years ago (50.4% “much worse”). The severe economic precarity many households in Lebanon face amid this downward economic trajectory is evident in the results presented in Figure 2. 32% of Lebanese and 60.3% of Syrian respondents report that their households lack the means to consistently afford food.

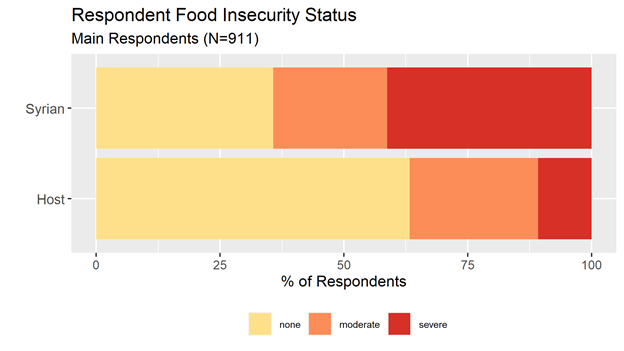

Widespread Food Insecurity, particularly among Syrians

In the face of these concerning economic conditions, food insecurity has arisen as a considerable public health concern. We assess the level of food insecurity in our sample by employing the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES), a survey tool used by the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) to assess food insecurity around the globe (see Box 2). Based on the FIES, Figure 3 displays the relative frequency of experiencing moderate and severe food insecurity for the 911 individuals that responded to all 8 questions required for the FIES assessment.

Figure 3: Relative frequency of food insecurity by sample strata, Source: TRANSMIT Lebanon Follow-up Survey, 2021/22

Based on the raw FIES score (see Box 2), 25.8% in our sample (Syrian: 41.3%, Host: 10.8%) are estimated to suffer from severe food insecurity.[2] Syrian respondents appear especially at risk. Nearly two-thirds of them display signs of either moderate or severe food insecurity. Particularly concerning: 78.3% of respondents reporting severe food insecurity live in a household with at least one child present.

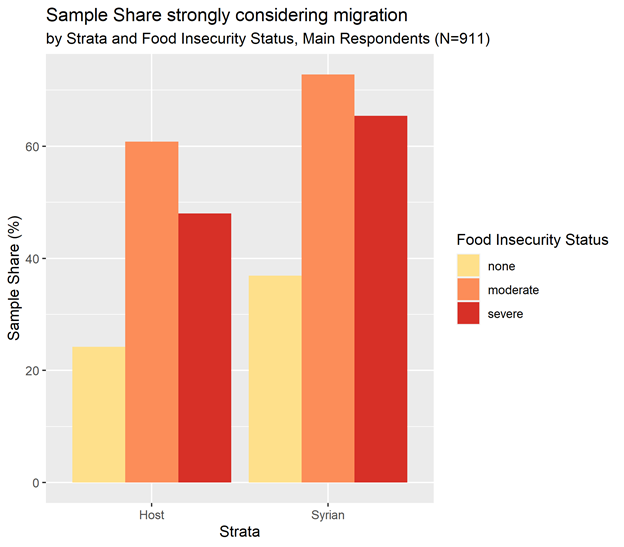

Many want to leave, few can

Given such unsustainable living conditions in the country, many individuals, particularly among the non-native population, are likely to desire a future outside of Lebanon. To capture such migration aspirations, we asked respondents to rate, on a scale from 0 to 10, how much they are considering migrating to another country.[3] In our sample, 37.3% of Lebanese and 58.5 % of Syrians report that they strongly consider migrating (i.e. reporting the maximum value of 10). As the results in Figure 4 illustrate, the experience of food insecurity is associated with a significant increase in the probability of strongly considering migration for both sample strata.

Figure 4: Relative frequency of strongly considering migration by sample strata and food insecurity status, Source: TRANSMIT Lebanon Follow-up Survey, 2021/22

For both Syrian and Lebanese respondents, experiencing moderate or severe food insecurity is associated with a roughly 30 percentage point increase in the probability of strongly considering migration (Syrian: 29.1, Lebanese: 30.5) in the probability of strongly considering migration.[4] Notably, respondents experiencing severe food insecurity appear less likely to express migration aspirations than those experiencing moderate food insecurity. The difference between the two groups is not statistically significant.[5]

Whether individuals are able to act on these migration aspirations, given the severe economic constraints many face, is doubtful.[6] Only 5% of respondents report having any concrete plans to migrate, only 6% say they would be able to come up with the equivalent of 399$ within a month.

Implications

The data presented here provides timely evidence on the socio-economic vulnerability of people in Lebanon in early 2022. The country's multilayered crises have led to considerable economic hardship and exposed a large part of the population to food insecurity. The situation is particularly precarious for the Syrian refugee population. Many refugees lack access to formal employment and thus a regular source of income, as well as the social, economic and political capital to compensate for economic shocks. Our results further show that, faced with deprivation, many consider leaving Lebanon, suggesting that they see no path to a sustainable livelihood in the crisis-struck country. Yet few of those unable afford sufficient food will be able to gather the resources necessary to safely relocate internationally. For many Syrian, returning home is not an option and irregular means of moving to third countries are often extremely dangerous, as the recent deaths of six migrants off the coast of Tripoli once more emphasized. The specter of large parts of the population being trapped in a state of prolonged material hardship and severe food-insecurity thus looms large.

Given these dire conditions at its onset, the additional shock of a drop in the global food supply resulting from the war in Ukraine could have catastrophic effects for the people in Lebanon. While a resolution of Lebanon’s multilayered crisis will require fundamental changes in the country's political structure, the current situation calls for urgent action both by the Lebanese political leadership, as well as the international community to extend aid operations and ensure a sustainable food supply under rising global food prices. Particularly the immediate dietary needs of families with children need to be met to avoid lasting health impairments. For the Syrian refugee population that finds itself caught between the unresolved Syrian conflict and the threat of hunger in Lebanon, assisted relocation options should be expanded.

While the attention of the global public has shifted (understandably) to the catastrophic developments in Ukraine, it is crucial that stakeholders and funders remain committed to ensuring sustainable livelihoods for the people in Lebanon and other vulnerable places, subject to the ripple effects of this latest global crisis.

Notes:

[1] Note: The data shared in this report is preliminary and remains subject to cleaning and minor revisions. It is shared in this preliminary state, because the authors deem the presented results as particularly pressing and relevant to immediate policy making.

[2] Due to systematic differences in response patterns between our and the FAO’s surveys, the raw-score approximation is likely producing an overestimate of severe food insecurity relative to the FAO’s global reference scale. Adjusting for these systematic differences using the Rasch Model results in prevalence of severe food insecurity of 16.8%, still significantly higher than the FAO’s estimated global prevalence rate in 2018-2020 of 10.5%.

[3] To distinguish it from more temporary forms of travel, we define migration as living in another country for more than 3 months.

[4] based on bivariate logistic regression in each sample strata.

[5] based on a 𝝌2-test of independence at 95% confidence.

[6] Comapre Safouane and Schaub (2021) for TRANSMIT results on migration aspirations and economic constraints.

Box 1: TRANSMIT – Transnational Perspectives on Migration and Integration

TRANSMIT is a migration research project of the DeZIM-Forschungsgemeinschaft and funded by the German Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth (BMFSFJ). The project studies the complex interplay of migration dynamics, migrant wellbeing and integration processes by building a transnational data-infrastructure that collects and links quantitative and qualitative data and knowledge on origin-, transit-, and destination countries. In addition to Turkey, TRANSMIT collects data in Lebanon, Morocco, Italy, Nigeria, Senegal, the Gambia, and Germany

Box 2: FIES - Food Insecurity Experience Scale

The FIES is a survey measure, consisting of eight yes-or-no questions and developed by the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) to monitor the prevalence of food insecurity around the world. For this report we are using the FIES raw score (i.e. the number of affirmative answers) to approximate the internationally comparable FAO scale in assessing food insecurity among survey respondents. A raw score between four and six corresponds to moderate, a score of seven or higher to severe food insecurity.